Newport in the 18th century embodied several marked ironies. One of early America’s leading slave communities, Newport and the Rhode Island colony were also founded on the principles of religious freedom. And as all prepared to separate from the tyranny of Great Britain, it also enjoyed vast economic prosperity through Indian and African slave labor.

Newport in the 18th century embodied several marked ironies. One of early America’s leading slave communities, Newport and the Rhode Island colony were also founded on the principles of religious freedom. And as all prepared to separate from the tyranny of Great Britain, it also enjoyed vast economic prosperity through Indian and African slave labor.

One religious and social phenomenon would bring great change for both master and slave. The Great Awakening was a Christian revitalization movement that swept Protestant America in the mid-18th century that brought a deep personal revelation of the need of salvation by and through Jesus Christ and accomplishing good deeds while on earth. A major by-product of the movement was to bring Christianity to Newport’s enslaved and free Africans. Scores of African men, women and children were converted during the Great Awakening period. At that time, ministers appealed to the enslaved and free Africans, preaching a message of hope and redemption while also catering to manners of worship that Africans carried with them to America, including singing, shouting, and dancing. In the present day, these activities are the very embodiment of African American churches.

By the eve of the American Revolution, hundreds of enslaved and free Africans are actively converted into the religion of their masters. This religious conversion while inspired by the sharing of the belief in one God, also served as a means of maintaining order and further assimilating slaves into European culture and work requirements.

“At one point in the colonial history of Newport, nearly or quite all the domestic servants were slaves, bound to their masters. In the eyes of an old Newport elder, who on the Sunday following the arrival of a Slaver from the (African ) Coast, thanked God that another cargo of benighted beings had been brought to the land where they could have the benefit of a Gospel dispensation.”

– Reminiscences of Newport, George Champlin Mason, 1884

Many Africans would in due course adopt their master’s religion. Slaves owned by Quakers worshipped at Newport’s Quaker Meeting House. The Rev. Mr. Honyman, of Trinity Anglican Church by his letter of June 13, 1743, “blesses God that his church is in a very flourishing and improving condition; there are in it a very large proportion of white people and an hundred negroes, who constantly attend the public worship of God.”

Slaves owned by Congregationalists heard sermons from the Rev. Ezra Stiles at his 2nd Congregational Church. Enslaved African woman Obour Tanner, with several historical accounts suggesting she originated from Senegal, would be baptized by Rev. Stiles on July 10, 1768. Later, she would become friend and mentor to Phyllis Wheatley of Boston, also from Senegal and the first African woman poet in America, who published her first poem in Newport in 1767 in the Newport Mercury. The slave Cato Brinley, was a “worthy member of the Baptist Church” who died “in the faith” while under the pastoral care of the Rev. Gardner Thurston of Newport’s Second Baptist Church.

Newport Gardner, aka Occramar Marycoo was an active member of Rev. Samuel Hopkins’s 1st Congregational Church. All of Newport Gardner’s children were baptized by Rev. Hopkins’s including:

| Silva | b. June 1, 1783 |

| Ahema | b. Nov. 15, 1787 |

| Charles Quamine | b. March 23, 1794 |

| Abraham | b. Nov. 8, 1795 |

Zingo Stevens was an active member of Rev. Ezra Stiles’ 2nd Congregational Church and he along with his children were baptized within the church.

| Zingo Stevens, servant of John Stevens | March 4, 1770 |

| Pompey Stevens, of Zingo | March 4, 1770 |

| Sarah Stevens, of Zingo | March 4, 1770 |

| Charles Stevens, of Zingo and Phyllis | November 10, 1771 |

| Prince Stevens, of Zingo and Phyllis | January 3, 1773 |

| Samuel Stevens, of Zingo and Violet | May 21, 1786 |

In addition, there are extant documents today that record the baptisms of slaves and later their children into their new found religious faith. But even in religion, Africans could only participate partially; most sat in balconies or in the rear of Newport’s places of worship.

As Rev. Hopkins becomes one of the early American leaders of the Great Awakening religious movement, he would also become the first great American Abolitionist as he preached fiery sermons against the evils of slave trading and ownership.

“We naturally look to you on behalf of the more than half a million of persons in these Colonies, who are under such a degree of oppression and tyranny, as to be wholly deprived of all civil and personal liberty, to which they have as good a right as any of their fellow men, and are reduced to the most object state of bondage and slavery, without any just cause.”

-Rev. Samuel Hopkins to the Continental Congress, 1776

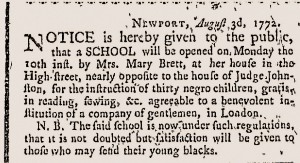

Newport Mercury August 3, 1772

Evangelical Christian Sarah Osborn, a leading member of Hopkins’ church, would actively interpret the teachings of the Great Awakening movement by providing religious and general education to hundreds of enslaved and free Africans in Newport during the mid-18th century. Like Osborn, Mary Brett with support from the Anglican Church would open a school for African children as early as 1772 that would last for several decades before being taken over by the free African community itself. And from Rev. Stiles’ personal diary entry from February 24, 1772 he reports that, “in the Evening a very full and serious meeting of Negroes at my House, perhaps 80 or 90. I discoursed to them on Luke XIV, 16, 17, 18. They sang well. They appeared attentive and much affected, and after I had done, many of them came up to me and thanked me, as they said, for taking so much care of their souls.”

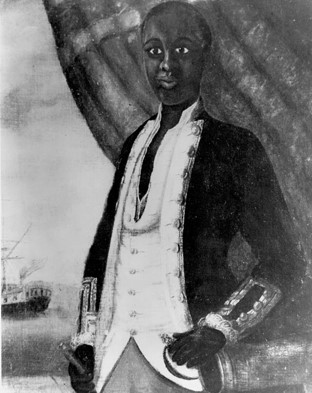

With a strong belief and desire to bring the Christian faith to the Africans, Reverends Hopkins and Stiles raised a considerable sum of money from various New England church groups with plans to educate and train as missionaries two Newport Africans for the purpose of sending them back to Africa. On November 22, 1774 John Quamino and Bristol Yamma of Newport were sent to the College of New Jersey (now Princeton University) under the education of the college President John Witherspoon. To prepare for the journey back to Africa, Hopkins and Stiles secured contact with a Reverend Phillip Qarque, an African missionary from the Society of London for the Prorogating in Foreign Parts, who was stationed at the Cape Coast Castle in Ghana. Amazingly, Qarque had also made contact with John Quamino’s uncle and mother who were from a prominent family in Annamaboe and were excited to reunite with their long lost relative thought to have been lost to slavery. Qarque suggested Quamino and Yamma go first to Liberia, but the entire plan ended with the start of the American Revolution. A surviving testament to their intellect and leadership, John Quamino would send a June 6, 1776 letter to Moses Brown of Providence thanking him for his courage to take on the abolition of slavery, where he stated,

“Having some late understanding of your noble and distinguished character and boundless benevolence with regards to the unforfeited rights of the poor unhappy Africans of this province and of your sundry petitions to the General Assemblies in their favor, has excited one of that nation, though an utter stranger, to present gratitude and thanks before you for all your excellent endeavours for the speedy salvation of his poor enslaved countrymen, and for what you were kindly disposed to do already of this kind in freeing all your servants. Hoping that you will be highly rewarded hereafter by Him who has promised to remember the merciful at the great reckoning day.”

Soon after, Quamino would be killed at sea on board an American privateer and Yamma would return to Newport and become a founder of the Free African Union Society. Quamino’s wife, Duchess and their children are buried in God’s Little Acre.